A Microscopic Secret Tumors Tried to Keep

For years, we’ve known that tumors are acidic. Most papers cite an average extracellular pH around 6.8, a bit lower than the normal 7.4. It’s been a foundational idea in cancer metabolism and drug development.

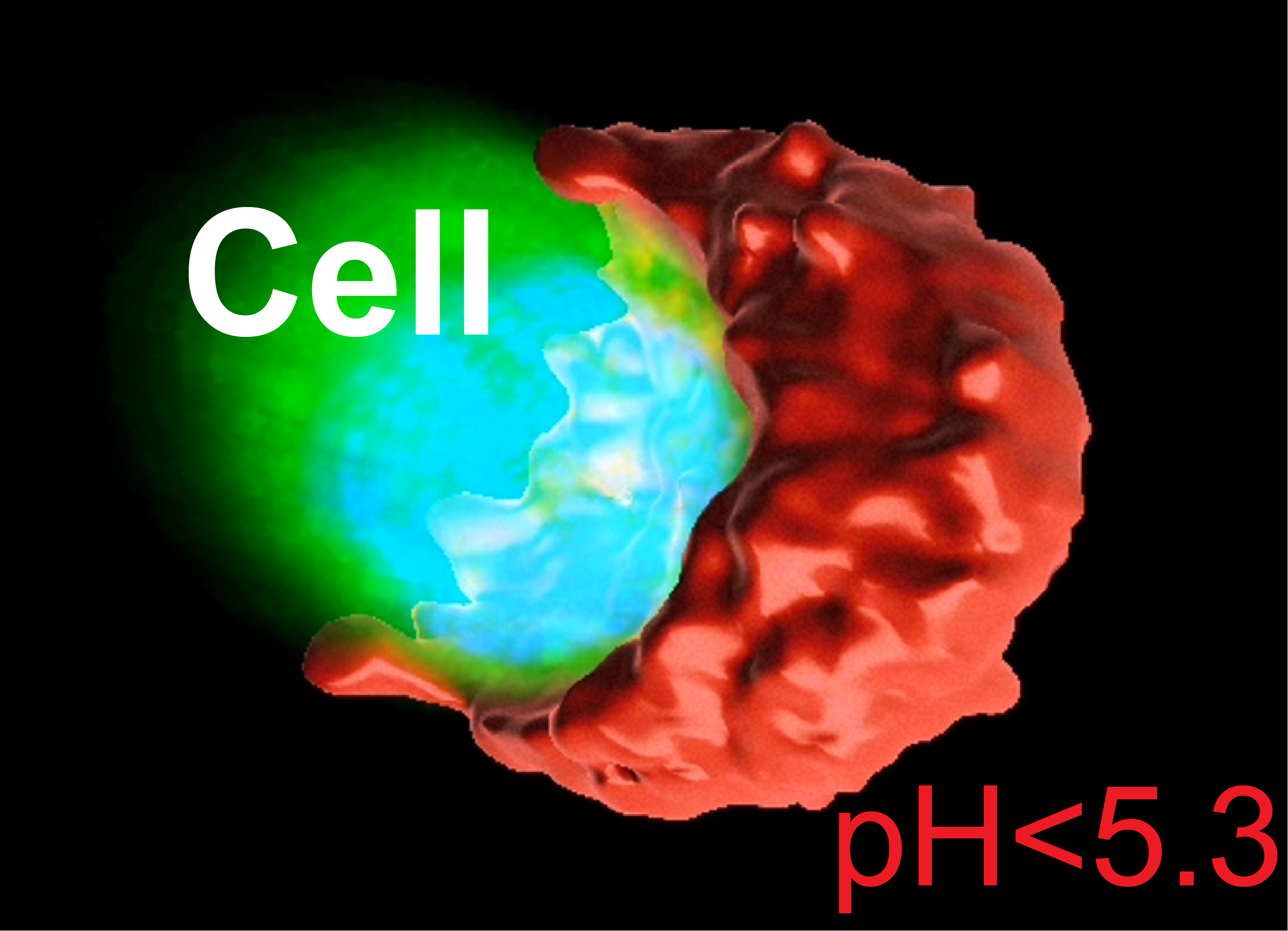

But when we began working with Pegsitacianine, a nanoprobe that only activates below pH 5.3, something didn’t add up. In clinical trials, the signal was strong—too strong to be explained by a pH of 6.8. If tumors were really that acidic, why hadn’t we seen it earlier?

So we took a closer look.

Using a series of ultra-pH-sensitive nanoprobes, each designed to switch on at different pH thresholds, we embedded tumor cells in a 3D gel and tracked where the acid went. What we found was not a gentle, uniform acidification, but a highly directional, creating a sharply acidic zone right next to the cell.

We called it SPEAR: Severely Polarized Extracellular Acidic Region.

Across different cancer types—lung, breast, head and neck—we saw the same pattern. Real patient samples showed it too. SPEARs form small, acidic “pockets” with pH < 5.3, far more acidic than what any average measurement would show.

And they weren’t just chemically interesting. These acidic spots were immune deserts. CD8+ T cells avoided them. In cell culture, we saw why—T cells died quickly in that level of acidity, while cancer cells didn’t seem to mind. SPEARs, it turns out, aren’t just acidic—they’re hostile to immune cells.

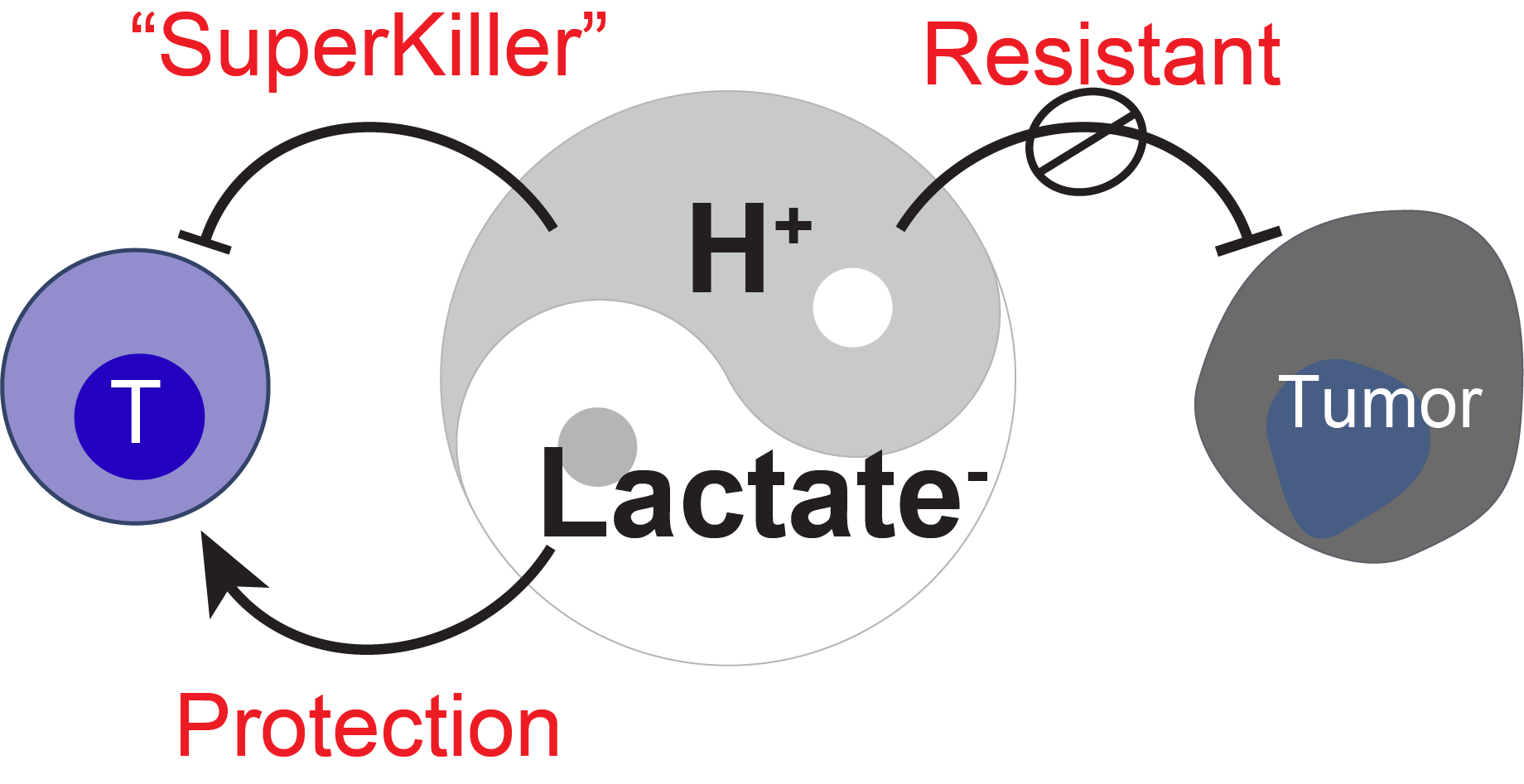

The mechanism pointed to monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), which export lactic acid. Block MCTs, and the acidity beam disappears. It’s a simple idea: tumors build sharp acidity gradients to push back against the immune system.

But here’s the twist. A couple of years ago, we published another study showing that lactate, the same molecule that’s exported alongside protons, can actually help T cells—if it’s separated from the acidity. In its neutral form, lactate supports T cell stemness and persistence in tumors.

So we’re looking at two sides of the same molecule. When coupled with protons, it’s immune-suppressive. When decoupled, it’s immune-supportive. Same metabolite, opposite effects—depending on the microenvironment.

In hindsight, it makes sense why average pH readings failed us. Tumors aren’t homogeneous; they’re patchy, asymmetric, and strategic. What we thought was a general “acidity” is actually a localized defense mechanism—a trench, not a fog.

This project started with an unexpected clinical signal and ended with a very physical insight: tumors are more precise in their metabolic architecture than we thought. Now, with tools like UPS nanoprobes, we can see their tactics—and maybe turn them against the tumor.

If we can target the SPEAR, we might be able to deliver therapies where they’re most needed—and where the tumor is most vulnerable.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: